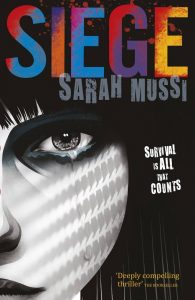

Leah Jackson is in detention. Then armed Year 9s burst in, shooting. She escapes, just. But the new Lock Down system for keeping intruders out is now locking everyone in. She takes to the ceilings and air vents with another student, Anton, and manages to use her mobile to call out to the world. Outside, parents gather, the army want intelligence, television cameras roll, psychologists give opinions, sociologists rationalise, doctors advise. And they all want a piece of Leah. Soon her phone battery is running out; the SAS want her to reconnoitre the hostage area…

Leah Jackson is in detention. Then armed Year 9s burst in, shooting. She escapes, just. But the new Lock Down system for keeping intruders out is now locking everyone in. She takes to the ceilings and air vents with another student, Anton, and manages to use her mobile to call out to the world. Outside, parents gather, the army want intelligence, television cameras roll, psychologists give opinions, sociologists rationalise, doctors advise. And they all want a piece of Leah. Soon her phone battery is running out; the SAS want her to reconnoitre the hostage area…

You get the picture. SIEGE is a book about a school shooting, and as such it was a very difficult book to write. At many points along the way, I nearly turned back, closed up my laptop and left the manuscript unfinished. It was difficult, because with every word I wrote, I had an increasingly eerie sensation that I was writing something prophetic.

I had to be brave to continue, and it was in part exactly because of its prophetic nature that I determined to continue and finish SIEGE. I felt a responsibility to those children yet to be slain, a responsibility to do everything in my power to avert another Columbine, Beslan or Connecticut from ever happening again.

There were three things that helped me to be brave – as brave a Leah, my heroine: firstly, was my belief that it is not the random, deranged, possibly psychopathic child who must shoulder all the blame for the shootings; secondly I wanted to reiterate concerns already raised by others about the state of our schools and the potential that they have to hot-house violence, and lastly to appeal to my child readers to let them know that they can make a difference, that they should speak up if they are worried about a friend or a family member – to let them know, through Leah’s story, they are not alone.

I have a suspicion it would be comforting to everyone if we could lay the whole weight of these atrocities at the door of the young men who pull the trigger. However, it is my belief that all of us are to blame. For when we don’t support those with mental health issues, when we don’t educate ourselves about personality disorders, when we don’t insist that government try a lot more vigorously to put systems in place to protect the most vulnerable, to resolve access to weapons, fund research into psychopathy, staff support centres for drug addiction and put in place counselling for families with members who suffer from anger management; when we as concerned others don’t actively confront and address things we know to be wrong or upsetting with the love and courage and truth and bravery needed; then it is we who allow these shootings to happen; for evil can only flourish when good men do nothing.

Secondly the level of violence in our schools: on gaming videos, on television and in our daily interactions with each other is terrifying. The subtext for any youngster growing up today is violence is ok. It’s ‘sick’, it’s ‘bad’ it’s ‘wicked’ and it’s ‘crazy’ (even in language we applaud it). So how can young people not feel it’s ok, when every evening they retire to their X Boxes and computer generated games and kill people by the dozen?

But finally and most importantly, I continued writing SIEGE for all the Leahs out there. You know who you are. All those young people who have a sibling, or a school friend who is ‘worrying’ – who can at times be violent and difficult and scary. I wrote SIEGE for all of you who struggle alone, trying to decide how to be – should I be nice to the ‘worrying’ person today; rude back; hit first; tell a teacher? To all of you, I want to say always tell a concerned adult that you are worried. You cannot face a ‘damaged’ person alone or solve their lives for them. If you say nothing you do not help them. You do not help yourself, or any other potential victim. The shooters of tomorrow, the bullies and the violent need help, not your silence or your secrecy. Don’t feel you’re a ‘snake’ or a ‘snitch’ or a ‘grass’ – because if someone had ‘told’ about one of the young men who pulled a trigger then maybe eventually someone might have listened and not only would he still be here, but so would his mother and all the innocent, beautiful children he sacrificed in his last and final horrific shout for attention.

But finally and most importantly, I continued writing SIEGE for all the Leahs out there. You know who you are. All those young people who have a sibling, or a school friend who is ‘worrying’ – who can at times be violent and difficult and scary. I wrote SIEGE for all of you who struggle alone, trying to decide how to be – should I be nice to the ‘worrying’ person today; rude back; hit first; tell a teacher? To all of you, I want to say always tell a concerned adult that you are worried. You cannot face a ‘damaged’ person alone or solve their lives for them. If you say nothing you do not help them. You do not help yourself, or any other potential victim. The shooters of tomorrow, the bullies and the violent need help, not your silence or your secrecy. Don’t feel you’re a ‘snake’ or a ‘snitch’ or a ‘grass’ – because if someone had ‘told’ about one of the young men who pulled a trigger then maybe eventually someone might have listened and not only would he still be here, but so would his mother and all the innocent, beautiful children he sacrificed in his last and final horrific shout for attention.

Yes, SIEGE was a difficult book to write. Yet I have never stopped believing that it was important for me to carry on. I started it over six years ago when I was teacher in south London and a stranger started living in the ceilings of a school I was working at, when a close family member had their first violent psychotic attack, and when a boy over the road was gunned down by a band of fourteen-year-olds. I have been living SIEGE for many years since then, and despite the shootings that have happened during them, sadly SIEGE is still prophetic and will remain so until we decide, all together, never to let it happen again.